2022 Census in the field

Across the street another country: the 2022 Census on the Brazil-Uruguay border

December 19, 2022 10h00 AM | Last Updated: December 28, 2022 04h15 PM

Highlights

- In Sant’Ana do Livramento, 500 km from Porto Alegre, you just have to cross the street to be in Rivera, Uruguay.

- DMC's geographic coordinates and physical maps help enumerators never to take the census outside Brazil.

- Brazilians, Uruguayans and doble chapas (citizens with both nationalities) coexist harmoniously. In 2010, the Census indicated 3,810 foreigners and 1,279 Brazilians naturalized in the city.

- Born in Palestine, Luana is one of the supervisors of the 2022 Census in the city, which has strong presence of Arabs.

The flags fluttering side by side indicate: half of the park is Brazilian, half, Uruguayan. It is through the International Park shared by the sister cities of Sant’Ana do Livramento and Rivera that enumerator Luciana Alves Cabreira Fernandes and supervisor Lucas da Rosa Rodrigues pass to reach the enumeration area where they will work on a spring morning.

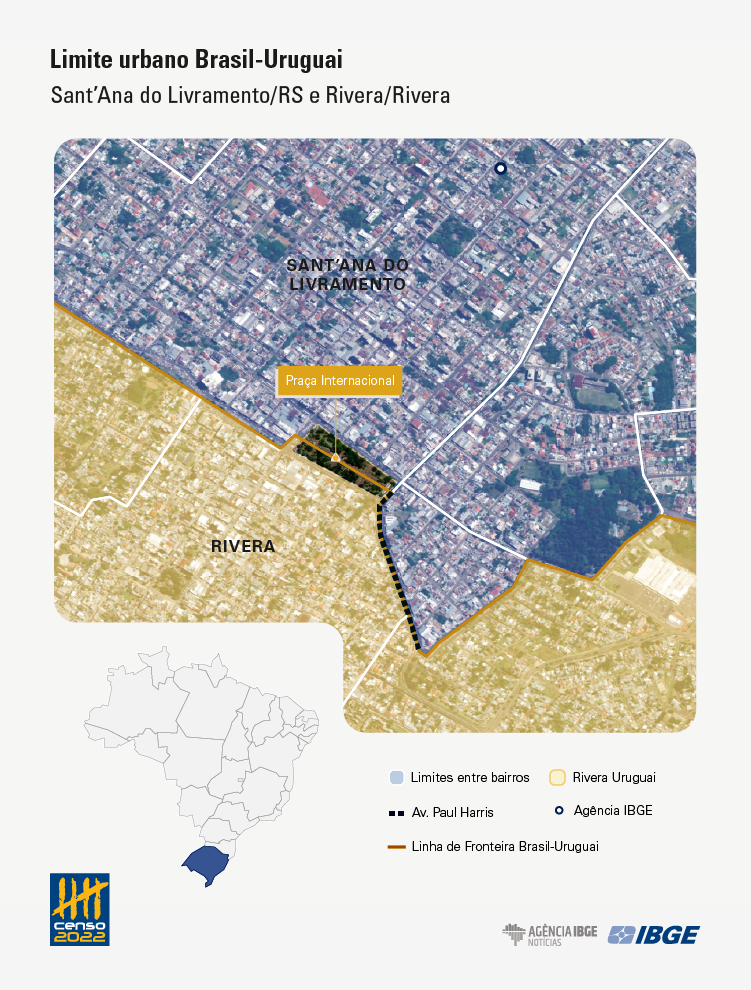

The work begins on Avenida Paul Harris, where a plant bed separates the two countries. From Brazil, it is possible to see the Uruguayan trade signs in Spanish. On the Brazilian side, a butcher shop announces that “hay vazio”, mixing the two languages and forming a third one that is very common there, "Portuñol".

Sant'Ana do Livramento had 82,464 people in the 2010 Census. Rivera, in turn, had 78,880 inhabitants in the Census carried out by Uruguay in 2011. Unlike many border towns separated by water, there are 160 thousand people who live together as if they were in the same country, crossing the border daily on foot to work, shop, visit friends and family, among other activities. This frontier poses some challenges for carrying out the 2022 Population Census, after all, it is necessary to enumerate the population living in Brazil, not in Uruguay.

On Avenida Paul Harris, in the central region of Livramento, it is simple to distinguish the two countries just by looking the plant bed. In regions where the state is less present, there are greater challenges. In the neighborhood with the suggestive name of Divisa (Division), a dirt road zigzags along an irregular pattern. Over there, the boundary milestones help to draw an imaginary line.

“Are we in Brazil or Uruguay?”, asked I to Anderson Rodrigues Paz, who is fixing a truck. “I think we are in Brazil”, answers he, looking at the milestone which indicates the border. I wonder if knowing it makes a difference. “On foot, no. By truck, yes, because of the documentation”, he explains.

Besides the boundary milestones, the IBGE has its own methods to prevent mistakes from happening. Mobile collection devices (DMCs) – equipment similar to a smartphone used by enumerators – capture geographic coordinates and, when enumerators try to open a questionnaire outside their enumeration area, they are alerted by the equipment. Enumerators and supervisors also go into the field with printed maps of their area.

There are rules so that the enumerators never make a mistake on their route. They should always start from a specific point in their work area and walk with his right shoulder directed to the houses and their left, to the street. In the case of Santana do Livramento, areas more susceptible to any doubt are being enumerated with great caution and always with the support of the Census coordination in the city.

Uruguayans, Brazilians and doble chapas

But, back to Lucas' and Luciana's work, right at the first house on their route they are greeted by a Uruguayan resident. It is a grocery shop with a house at the back. The resident and owner of the establishment kindly assists the IBGE team and answers the questionnaire, but says she does not like to give interviews to the press. Turning the corner a few minutes later, in an apartment with a view to the International Park, another Uruguayan, Selva Rodriguez Perazza, talks with the reporter of the IBGE News Agency.

Retired from Rivera City Hall, Selva has lived in Uruguay all her life. However, after the death of her husband, she moved to Brazil to be closer to her son, who lives in Livramento and has Brazilian citizenship as well as Uruguayan citizenship – citizens that the local population calls "doble chapas" for having both documents. “He told me: mama, come to Brazil. It's more beautiful, you'll have a beautiful view. It was easier to see him. I love Brazil, I used to go to Florianópolis when I could. Not now because I'm sick. I watch Brazilian (television) channels,” she says. For Selva, the fact that they are two different countries is almost irrelevant in the daily life of the population. “The cities are so close that you don't even notice”.

Enumerator Luciana comments that she has interviewed many Uruguayans, and has been kindly welcomed by them, although some believe they do not need to be enumerated. “They think they don't need to be counted in the Census because they are Uruguayans. So we explain that, if you live in Livramento, you need to be censused”.

Language is not a barrier to understanding. “There are people who come here who think it's different. For those of us who live here, who grew up here, it's normal. We speak both languages, we're used to it”, explains retiree Antônio Miranda. He is Brazilian and welcomed us at the gate of his house in the Divisa neighborhood, holding the chimarrão cup and speaking good Portuguese.

A few miles away, housewife Lenir talks at her front door, where she can see Uruguay on the other side of the street. The Brazilian mixes Portuguese with expressions like "bueno" or "no más". “It's very good, we consider it as a single city. You see that I speak a mixture. People here live like this”. Lenir's husband is Uruguayan, but has always worked in Brazil. The couple has lived on the Brazilian side for 18 years and lived for 23 years in the country that starts across the street. “My son is only Brazilian and my grandson is only Uruguayan”.

In the Divisa neighborhood, the reporters covered the work of Marco Aurélio Costa, 75 years old, the oldest enumerator in Livramento. “It's a very good experience, because we interact with several people, and it adds to us as a citizen, we see reality, the contrasts”, he says. Born in the border town, Marco Aurélio lived for 28 years in Pelotas (RS), where he worked in industry and taught Statistics. He returned two years ago to Livramento, or rather to Rivera. “I live in Rivera and my wife is Uruguayan,” he says.

Among those interviewed by Marco Aurélio is the double chapa Silvia Jacqueline. Born in Uruguay, Silvia has lived in Brazil for 20 years with her husband and both obtained the Brazilian document a few years after settling in Livramento. “We have a house here and it helps us a lot to have the Brazilian document”.

Sant’Ana do Livramento is equidistant from the capitals of Rio Grande do Sul and Uruguay. About 500 kilometers separate it from Porto Alegre and Montevideo. It has an area of almost 7,000 km² – the second largest municipality in Rio Grande do Sul – of pampa biome, suitable for livestock. The municipality has the largest flock of sheep in the country, with more than 400,000 head. There are also around 400,000 head of cattle, which makes Livramento among the 50 Brazilian municipalities with the largest cattle herd, according to data from the 2021 Municipal Livestock Survey.

In the urban area, tourism stands out thanks to the freeshops on the Uruguayan side, where Brazilians can buy tax-free products, which attracts people from all over Rio Grande do Sul. Tourism activities, however, usually fluctuate along with the exchange rate. When the real appreciates, more tourists look for the city. On the other hand, when the Uruguayan peso appreciates more, Uruguayans cross the border to shop in Livramento's shops. The dynamics of the exchange rate also affects the real estate sector, which is why many in Livramento are betting that the number of Uruguayan residents in the city will be higher in the 2022 Census than in 2010, since it is cheaper for Uruguayans to live in Brazil.

In the 2010 Census, there were 1,279 naturalized Brazilians in Santana do Livramento. In addition, there were also 3,810 foreigners. Thus, 6.17% of the city's population was not born in Brazil. The number is much higher than the Brazilian average: in the whole country, only 0.31% were born outside the country.

From the Middle East to the Pampas Census

Not all foreigners and naturalized Brazilians come from Uruguay. As in several border cities in Brazil, Santana do Livramento has an expressive presence of Arabs.

“Here business is very dynamic. Anyone who likes to trade, and Arabs generally do, settles on borders, and not just in Rio Grande do Sul,” explains Raed Shweiki, merchant and vice-president of Livramento's Trade and Industry Association (ACIL). “Borders are great land ports. Foz do Iguaçu has a large migration of Arab community, because generally you can do business easier. In Livramento you will see many Uruguayans coming from the countryside of Uruguay to buy here on a weekend and then you will see that it is attractive for those who work in the trade”, he adds.

Raed is not among the more than 3,000 foreigners in the city. He was born in Brazil, the son of a Palestinian father and a Jordanian mother. The store where he receives the reporters was formerly just a part of the property, the family lived in another part. “In the old days, you would start out as a peddler, found a little shop and grow. We used to live in this store. Then the store was practically a quarter of what it is today. And then we expanded the store, we opened another one, and so on”, he says. On the other side of the border, the Arab colony also owns most duty-free shops.

The merchant explains that the Arab community is already in its fourth generation in Livramento, but that more immigrants from countries like Syria, which is going through a conflict, continue to arrive. “The first wave was of Lebanese immigrants. And the Palestinians came after the war, after the creation of the State of Israel (in 1948). Now people are coming from Syria. Usually people leave when there is instability in their country or religious persecution, political persecution. The new generations no longer work only with commerce. There are doctors, lawyers, engineers”, he says.

According to the 2010 Census, there were 311 people who professed Islam as their religion in Livramento. The number, although small (corresponds to 0.38% of the municipality's population), is much more significant than the Brazilian average. In the whole country, only 0.02% of the population was Muslim in 2010. It should be noted that not all Arabs are Muslims, there are many Christians. Raed estimates that there are between 800 and 1,000 people from Arab countries and their descendants in the city.

Census 2022 supervisor Luana Halima Gandhe Judeh is one of them. Born in Palestine 23 years ago, she migrated to South America in 2011. She first lived in Rivera and currently lives in Livramento, and has three nationalities: Palestinian, Uruguayan and Brazilian.

“Luana is a Brazilian name, because my grandmother wanted it, she watched Brazilian soap operas”, she says. Her grandmother had lived in Brazil before, then returned to Palestine. “My grandparents came here in 1948, when the war started to get a little tighter. They passed through Uruguaiana, Santa Rosa, Canela, Quaraí (all four cities in Rio Grande do Sul)”. In 2011, Luana's parents decided to return to the border between Brazil and Uruguay in search of better living conditions, working in commerce. “My father decided to go back to the border because there was the movement of the Uruguayans, the commerce”. An aunt of Luana works in the commercial sector in Uruguaiana, a city in Rio Grande do Sul that borders Argentina.

Having arrived in the country in 2011, Luana had never seen a Population Census take place. “I didn't know about the existence of the Census. When the IBGE selection process came out I could understand what it was. I ended up getting in for the experience. I have a degree in Law, I graduated this year, and I thought that maybe my background would help in some way ”, she analyzes, as she walks to another interview, working for the service of Brazil.