From mountain ranges to pampas, Rio Grande do Sul features diversity in Census of Agriculture

December 18, 2017 09h00 AM | Last Updated: June 05, 2018 03h49 PM

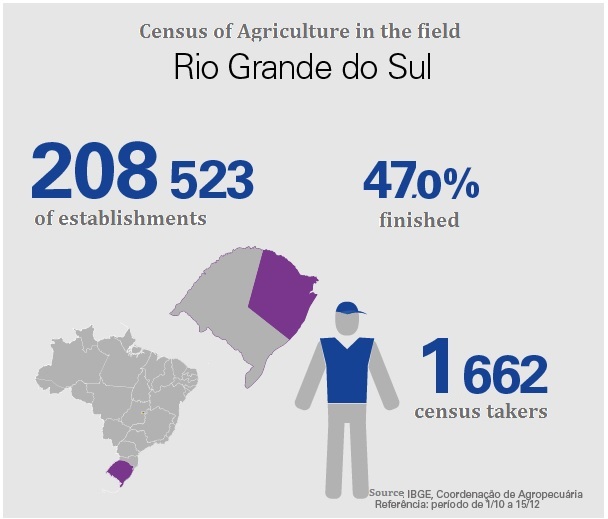

The agricultural diversity in Rio Grande do Sul poses the major challenge for the Census of Agriculture 2017, which is now in the third month with 47% of the collection completed. In the mountain range area and in the north and northeast of the state, small properties prevail, with a great deal of products, whereas, in the southern half and on the west border, there are larger establishments, usually dedicated to monoculture, traditionally rice or livestock farming.

Such diversity affects the census operation in the state. "In the areas of small family properties, the census taker has a great number of establishments within a smaller area, which facilitates the coming and going between the properties in much less time, whereas the interview lasts longer due to production diversity. On the other hand, in the areas of large establishments, the distance is longer and the number of properties is lower. But questionnaire filling takes less time because there is usually only one kind of farming", says operations manager of the Census of Agriculture in Rio Grande do Sul, Luís Eduardo Puchalski.

Rio Grande do Sul, major national producer of grapes, rice, sweet potato, tobacco and wheat, according to the IBGE's Municipal Agricultural Production (PAM) of 2016, has farming as the central point of its economy. Family farming is responsible for the biggest part of the state production of beans, corn, cassava and cow milk, products which are part of the daily meals of families in rural and urban areas.

In the collection, most of census takers ride motorcycles or bikes, but there are places where they go walking, riding a horse or even a boat, as in the islands of the Jacuí river and in the region of Rio Grande, in the southern coast of the state. With a motorcycle, census taker Marcírio Leite crosses the countryside of Sant'Ana do Livramento, on Uruguay's border. In the first two weeks working in the collection, he had already covered 1,080km. "I've worked in other censuses...we have to realize, understand, see things, otherwise we are going to miss a lot", he says.

Census taker Marcírio Leite interviews rural producer in Rio Grande do Sul

Wheat and rice and the food produced for the domestic market

Farmer Kalinton Prestes, from Fetag/RS (Rio Grande do Sul Family Farmers Federation, under Contag), highlights the importance of encouraging food production for the domestic market, a policy that favors small farmers, besides providing cheaper products for the local dwellers.

However, products such as rice and wheat have been losing room in the last years for soybeans. Data from PAM show that 2016 was the year with the smallest planted area for wheat since 2007, despite the fact that production was the third biggest in the period.

According to the president of Fecoagro-RS (Federation of Agricultural Cooperatives of the State of Rio Grande do Sul), Paulo Pires, crops like wheat and rice make farmers feel unsafe, mostly because of the weather, which causes production to vary constantly.

"Many people think that farmers prefer monoculture, but this is not true. Soybeans have greater liquidity and make the farmer feel safer. Therefore, it would be important to design and promote public policies that stimulate the production of food for domestic consumption, such as rice and wheat," explains Pires, who defends as an alternative the creation and expansion of public programs of agricultural insurance.

Taxes and import issues also interfere in local production. According to Kaliton, many farmers find it difficult to continue working because of the "high cost of production and the low compensation, which shrinks everytime the government imports wheat from other countries via Mercosur."

Even so, wheat and rice are still significantly important in the state. Data from PAM reveal that the production value of paddy rice was R$6 billion, whereas that of wheat reached R$1.3 billion in 2016. The last edition of the Census of Agriculture, carried out in 2006, showed that there were 19,766 agricultural establishments destined to the production of wheat in Rio Grande do Sul: 14,379 belonging family farmers, according to the criteria defined by Federal Law 11,326/06. Rice was present in 11,967 agricultural establishments, with 7,176 of them being family farmers.

The advance of soybeans for export is even more significant in the region of corn crops and in the areas that used to be dedicated to cattle raising pastures in the pampas, as highlights by operation coordinator of the Census of Agriculture, the agronomist Luis Eduardo Puchalski. Data from PAM reveal that: in 2016, corn had had the smallest planted area or area to be harvested (740 thousand hectares) since 1988, when this piece of information was first investigated. In 1992, the planted area or area to be harvested rose above 2 million hectares in Rio Grande do Sul.

Peruvian farmer Fernando Rotondo shows his olive crop

More incentive to keep youngsters in the countryside

A concern of the entities in the sector is how to create opportunities for the young people to stay in the countryside. Data from the last Census of Agriculture already had shown that the general profile of the owners or head of the agricultural establishments in Rio Grande do Sul was of men aged between 45 and 55 with incomplete secondary education.

For Kaliton, it is possible to rise above this situation with the support of the government giving access to health and education in the countryside, making investment in telephony and internet access, as well as improving the road transportation infrastructure. He highlights that it is also necessary to have "efficient policies for the rural young people, offering the necessary conditions for them to buy land."

Rural succession pops up in the Census collection: "it is still to be confirmed, but there might be a decrease in the number of agricultural establishments in the state. Census takers have bumped into places where there used to be establishment in 2006, but today are just places of residence for retired old people of the rural zone, where there is not any king of trade anymore. The production is just complementary, not featuring subsistence, because the provisions of the family come from the retirement pension, explains Puchalski.

The Census coordinators also tells that, in areas where it is possible to plant soybeans, retired farmers end up renting their lands and getting extra income, although that does not happen in mountain areas, where the terrain is steep.

Olive crops are increasing in the Rio Grande do Sul's fields

New crops

Not only traditional crops in the south of the country are present in the Census. New income alternatives in the rural area were included in this edition of the survey. It is the case of pecan nuts and olive crops or the production of olives and olive oil.

"Pecan nuts and olives were nor included neither coded specifically in the Census of Agriculture of 2006, but the Municipal Agricultural Production revealed a higher number of such cultures and we included codes for them this time", explains the technical coordinator of the Census of Agriculture of the State Branch of the IBGE, Cláudio Sant'Anna.

An example of that is farmer Fernando Rotondo, a Peruvian that quit his job in a multinational in the herbicide business in São Paulo in 2009 and started planting olives in Sant'Ana do Livramento, together with his wife. In addition to the crop, he has nurseries and a small plant with machinery imported from Italy in a property of 30 hectares. As a whole, there are 10 thousand plants, with nine kinds of olives.

Favorable weather and the economic issues were crucial for the choice of the area. "The crop demands a lot of dedication of the producer and takes a time to generate financial return, it is not an easy crop", highlights Rotondo, who also advises that there are people changing from livestock farming to olive growing. "They are completely different, the level of involvement is much bigger". The plant enters the productive phase usually after four years, and the productivity is very weather dependent. "We live on that, we live on this farming. We live here", he concludes.

Text and images: José Zasso

Infograph: Pedro Vidal