Retratos Magazine

Art in maps shows transformations from colonial Brazil up to the present

August 12, 2019 10h00 AM | Last Updated: August 21, 2019 06h10 PM

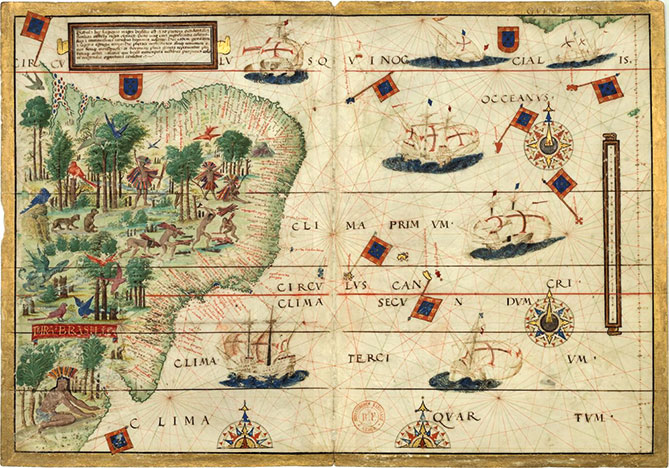

Far beyond representation, maps from the colonial period of Brazil display information about imaginary times and disputes over territory. A PhD in Visual Arts and an Art History professor, André Dorigo has conducted an extensive master's research approaching the differences between cartography in Portugal and its counterparts in the Netherlands, Spain and France, in the colonial period.

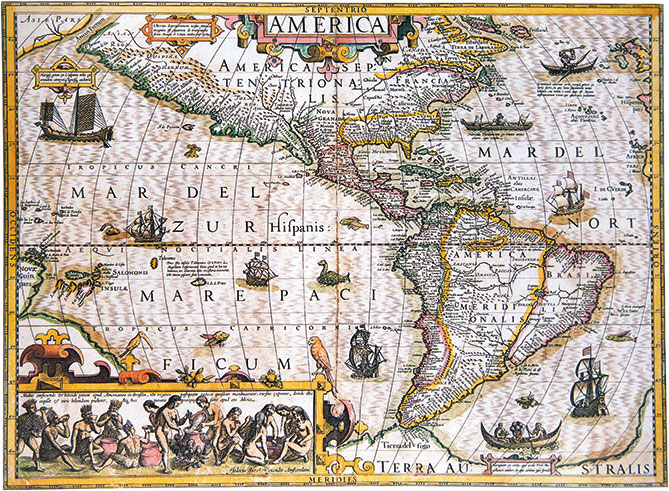

According to André, there was a political dispute for information: on the one hand, the Portuguese maps were handwritten and completely secret, in order not to make foreigners greedy for our land. The Dutch, having bribed Portuguese cartographers, would print and distribute maps with information acquired from them. “Portuguese cartography has to do with the mode of colonization: commercial, pragmatic and economic”, Mr. Dorigo explains.

Given the need to know and protect the coast, at the time it was common to have a more accurate description of that part of the territory. André Dorigo mentions maps with an almost completely defined drawing of the coast, very similar to what we have today. “Of course, a lot has already been improved, but that one was really similar. It uses toponyms, provides the names of landforms, latitudes, the compass rose and other scientific discoveries”.

An interesting fact about maps at the time is the mix between imaginary and real information. Amanda Guerra, a geographer at the IBGE who wrote her master’s thesis on historical cartography, explains her maps always portray the human view of the space they live in.

She mentions as an example the maps of the Middle Age (between centuries V and XV), which represented the world under Christian lights: “right in the middle of the world one would find Jerusalem. The East, considered a paradise was placed on the upper area of the map.”

At the time Europe was discovered, maps presented more scientific features, though some imaginary figures like sea monsters were still found in the empty areas of maps. “As time went by, those images gradually disappeared as maps gained a more scientific nature,” Ms. Guerra says.

Aesthetics and science

The maps of the colonial period were real works of art. The specific style of each drawing could easily reveal the author of a map – who could be compared to an artist signing his works.

Nevertheless, the marriage between Science and art weakened in historical periods such as the Illuminism and the Modern Era, as a separation between what is scientific and what cannot be classified as such was clearer each day – and that also affected art. Since then, the beauty of maps has been replaced by strict standardization derived from technological and methodological advances that have been observed since the colonial period.

Nowadays such separation is not as strict and new forms of representation have appeared. Amanda Guerra and André Dorigo agree that, among current cartographic products, the maps have acquired much more aesthetic freedom and information can be displayed in a clear yet more ludic way.

One of the advantages of this new format is its reach. It is useful for the public in general but the quality of information is maintained. As André Dorigo, it is all a matter of reading.

“Plants and charts are scientific and pragmatic elements with a specific use, but maps are more flexible in terms of representation, more open to art. Yes, maps can aim at communication, with a balance between the scientific and the artistic.

That is why the IBGE produces beautiful maps. I do think maps can provide the public with proper geographic knowledge,” the professor adds.

The complete article is available at Retratos Magazine no 17.