Retratos Magazine

The art of sericulture gains ground in the country

April 17, 2018 09h00 AM | Last Updated: June 05, 2018 11h01 AM

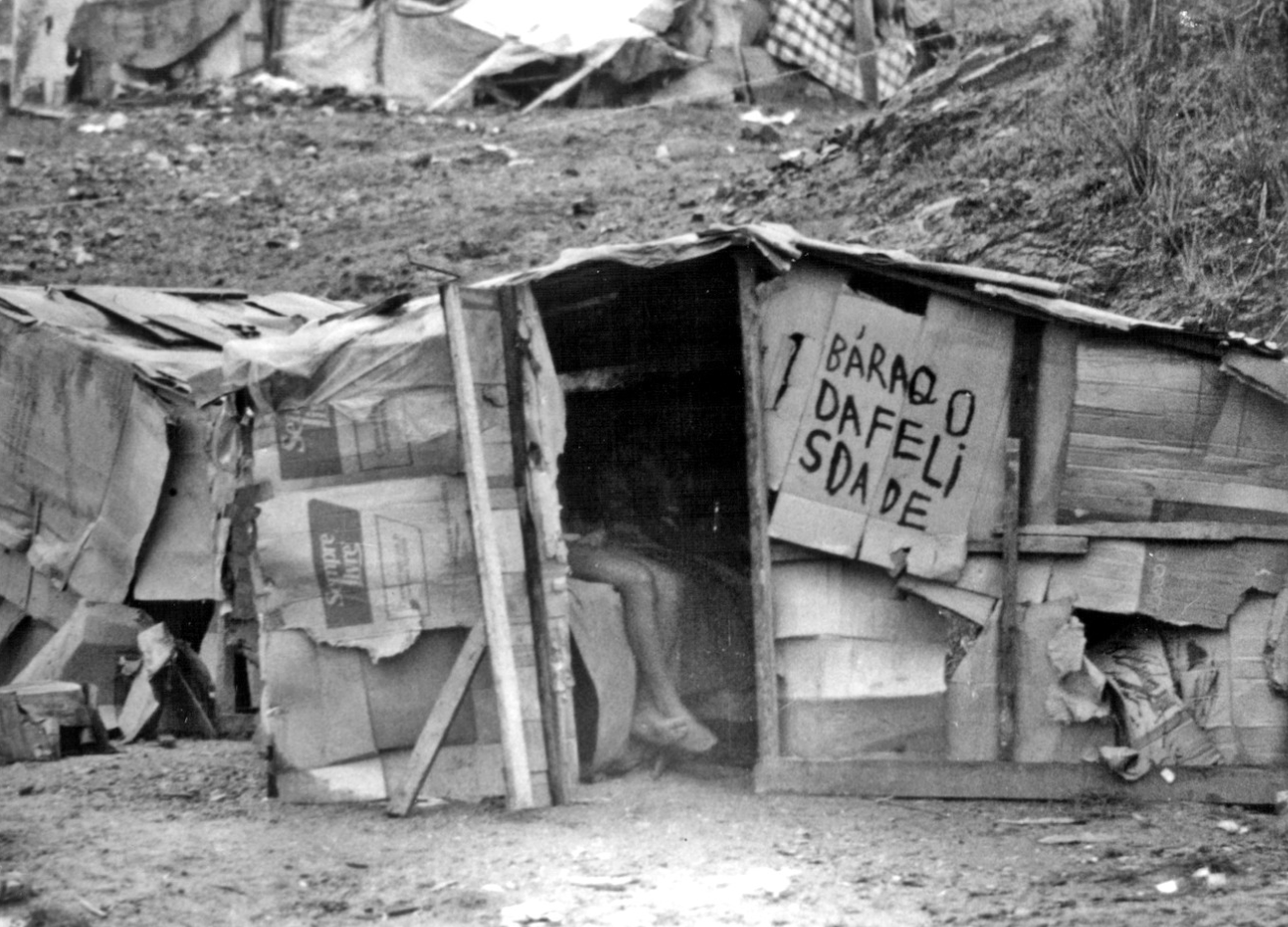

Discovered nearly 4,500 BC and kept secret for centuries by the Chinese, the silk production technique is now mastered by several countries. Called sericulture, the activity consists of silkworm farming for yarn production. The yarn was once as worth as gold, had trade routes between China and Europe named after it and is currently one of the most coveted products by the fashion industry. Brazil, far away from all this millennial tradition, started the sericulture only in the nineteenth century. Over the years, the country has gained international visibility in the production of silk thanks to the quality of its yarn, which is considered the best in the world.

It comes as no surprise that the silkworm originates one of the thinnest yarns there is. However the way the production chain of the sector works remains a mystery for many people. It all begins with the reproduction of the silkworm butterflies, called scientifically Bombyx Mori. The procedure is totally controlled by man and occurs in the Bratac's farm, in Londrina (PR) - the only company supplying larvae and producing silk yarn in the country.

Each female lays between 500 and 600 eggs, which generate the larvae that will weave silk yarns around themselves, forming a cocoon.

From birth to the end of this cycle, the caterpillar goes through five stages of development. In the third stage, with seven days of life, the caterpillar gets some extra help of a little more than 2,000 silk farmers in Brazil, offering it adequate structure and feeding so that the larvae can grow and weave good cocoons. With the favorable weather - temperature between 20 and 30 degrees Celsius - this work of the producers lasts around 25 days, when the cocoons are harvested and sold. To keep the yarn intact, the animal is sacrificed while it is still within the wrapper and then sold to large animal feed manufacturers. The silk yarn, in turn, is unrolled and exported to countries like Japan, Korea, France and Italy.

"Today the fashion world uses the Brazilian yarn because it is the best quality there is," says the agricultural technician of the Emater Institute and manager of the Technical Chamber of the Silk Complex of the State of Paraná, Oswaldo da Silva Padua. According to him, weather, soil care and genetic improvement of caterpillars are some of the aspects that reflect on the superiority of the cocoons produced in Brazil, which have on average 1.2 km of uninterrupted silk yarn with no defects.

Data from IBGE's latest Municipal Livestock Survey show that, in 2016, Brazil produced 2.8 thousand metric tons of silkworm cocoons, ranking fifth in the world production, behind China, India and Uzbekistan and Thailand. Paraná leads the national production with 83%, followed by São Paulo (12%) and Mato Grosso do Sul (5%).

Making a family's living from sericulture

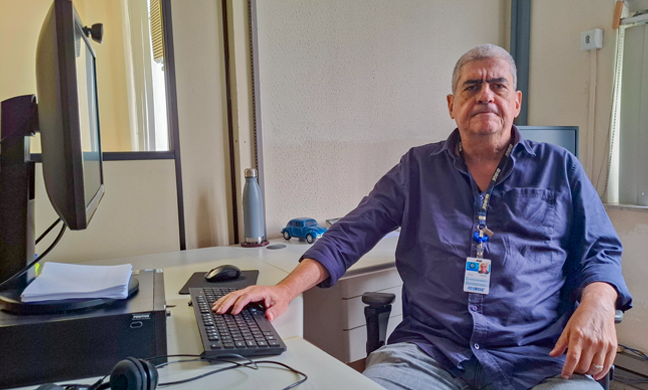

At Antonio Dosso's family farm, day say begins well before the roosters crow. At 3 o'clock in the morning, his son-in-law Dirceu is already on his feet, with about 320,000 larvae of silkworms growing in his two sheds. "I come here first, take care of the worms and then I cut the mulberry," says the farmer, who feeds the caterpillars five times a day on mulberry leaves - the only food that the animal eats.

The activity on the farm began in 1985 and since then has been making the family's living. "Coffee growing was over and we started with the silkworm," says Antônio, at 75 years old. Today, with some health problems, the responsibility to take care of caterpillars is not his anymore, but his daughter's, Aparecida, and Dirceu's. His wife, Maria, still helps a lot with the job, but confesses that "it is not easy to run such a shed."

The family lives on a farm in Nova Esperança, northwest of Paraná. The municipality is part of the Vale da Seda (Silk Valley), composed of 29 cities and acknowledged for being the largest production center of silkworm cocoons in the west. In the region, the silkworm farmers produce up to 10 crops of the animal in the year. In the colder months, production is suspended because the mulberry trees fall into dormancy and the caterpillars stop feeding, damaging the yarn formation.

Today, on the farm, about 600 cocoons (one kilo) are sold by the producers at R$21. The price varies according to the quality of the raw material and yields good fruits for those who dedicate themselves. "Today I have a house, a car in the garage, kids studying, eating, living. You don't get rich, make no mistake about it. But you pay your bills," says Dirceu, who has his daughter Gláucia studying at a private school and pays law school for his son Douglas. The children do not intend to work in the farm.

Challenges and innovation

Sericulture in Brazil is a very organized activity, but that has been losing ground throughout time. In ten years, the production of silkworm cocoons in the country fell by 36.2%. "We are working to develop alternatives to make the youngest aware of the importance of family succession," says Oswaldo, who works at the Technical Chamber of the Silk Complex of Paraná. The body is made up of representatives of the state government, the Agronomic Institute of Paraná (IAPAR), universities and sericulture associations. "It is the Chamber that pass government programs to improve the entire production chain in the sector, enhancing the technical assistance, rural extension and research," says Oswaldo.

Also in Paraná, the State University of Maringá (UEM) keeps the only public silkworm germplasm bank in the country, being a reference in research on the subject. "The laboratory works in partnership with researchers from England, Canada and France, as well as from Latin American countries," says Professor Maria Aparecida Fernandez, who coordinates the Department of Biotechnology, Genetics and Cell Biology at UEM.

Among the advances obtained by the researchers in the preservation and genetic improvement of the species are the identification of highly productive breeds and the effects of insecticides, applied in crops, on silkworm productivity.

Currently, one of the researches in progress investigates the production of colored cocoons, obtained from the use of dyes in the feeding of caterpillars. The novelty would reduce one of the most polluting chemical processes ever: the subsequent dyeing of the tissue, which produces large volumes of toxic waters, often untreated before being returned to nature. "Achieving the production of colored silk by natural processes without the need for dyeing would be extremely important for the continued development of the textile industry, without causing any damage to the environment," says the teacher.