Goat and sheep farming stands out in Ceará

January 15, 2018 09h00 AM | Last Updated: January 17, 2018 11h05 AM

The sertão (*) of Ceará produces much more than one can find at first. The state has gained prominence in livestock, mainly in goat and sheep farming. According to data from the IBGE's Municipal Livestock Production (PPM), Ceará had, in 2016, the fourth biggest herd of goats in the country: 1.13 million head. The state was in the same position regarding sheep, with a total 2.31 head. Tauá is the municipality in the state that has the biggest herd of sheep and goats, with approximately 6% of the state production in both cases. In 2006, according to data from the last Census of Agriculture, the state had 38,114 agricultural establishments which dealt with goats.

Klinger Aragão, a servant at the Goat Division of Embrapa (**), highlights that “the herd of sheep reached, according to data of 2016, the same level as that of cattle herd, a previously seen occurrence in more than 40 years, for cattle raising had always been the main livestock activity, being even relevant in the process of occupation of the state”. According to Mr. Aragão, goat farming is not as important yet, but has improved in the latest decades.

There has been steady increase of this livestock segment in Ceará, and producers wish to obtain updated information to support their decisions. The 2017 Census of Agriculture has been in the field since October, and producers expect to see, in the results of that survey, a precise and updated portrait of the changes the sector has been going through.

The staff that works in data collection

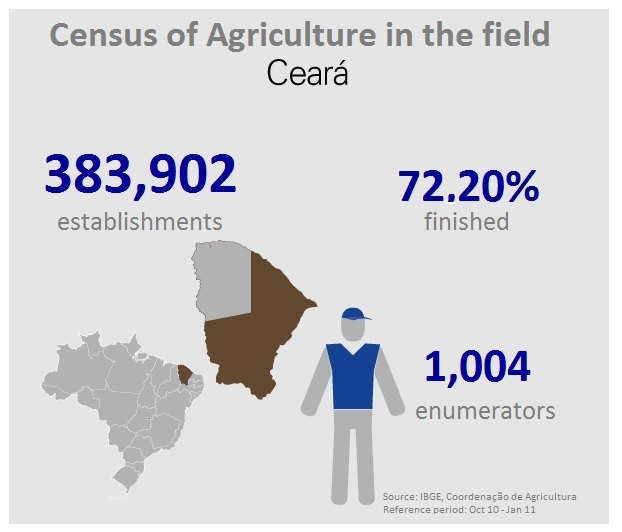

More than 277 thousand establishments have been enumerated in Ceará. That corresponds to 72.2% of the overall number (383,902) estimated by the IBGE. “It has been a great experience, we get to the localities selected and everyone recognizes us because the operation is being well publicized. Supervisors have been to radio programs,” points out Railan Bernardo, age 27, who rides a motorcycle to collect data from his enumeration area.

Railan was born in Parambu, a municipality near Tauá. He tells us he has been living in the city with his wife and daughter for two years, in order to finish his undergraduate course in Chemistry at the State University of Ceará (UECE). That is the first time he has worked for the IBGE, and he sees that as a very positive experience: "It is a well organized institution, they provide good assistance and our supervisors are always there to help us. I used to be unemployed, my wife was the only one working for some time”.

Possidônio Netoli has lived in Tauá for about a year and a half as an enumerator. That is not his first time at the IBGE, though. He took part in the data collection for the 2006 Census of Agriculture in his hometown, Crateús, 149 km away from Tauá. That was his first job. At the age of 18 at the time, he found hs own way to do the job: “I did not have a car, so I used to take the bus, get a ride, ride a bike or even walk to my place of work”.

According to Possidônio, empathy and patience to speak to the person being interviewed are essential characteristics for an enumerator. Although there is no landowner in his family, Possidônio sees, in his father-in-law, an example of a fieldworker and his everyday effort: “He goes without food to be able to buy feed for his animals, so we see how much he cares for his work, and so do the other producers. They go without good clothes or fancy food just because they love so much what they do”.

Producers' perspectives

Francimar Batista has raised goats since 2000, but only in 2011 did he start milk production with the help of project Dairy Goats. The day in his property starts at 5 o'clock in the morning: “The first thing we do is to milk the animals”. Francimar Batista inherited the land from his grandfather, who had started dealing with cattle and sheep in 1975. Bulls and cows remained, but the sheep are no longer present in the property, because, according to Batista, “they are very demanding".

The producer lives with his parents, and the investments in milk production help them have more regular income rather than counting only on the sale of animals. Francimar thinks milk in not beneficial to his family only, since the beverage is directed to "malnourished children”, being processed and distributed by the city government.

According to Francimar, production has become more difficult each day. The drought has forced producers to find ways to produce more with fewer animals. Producer José Alexandrino has been facing similar difficulties, especially the scarcity of water, a vital element to the growth of animals. Alexandrino says he has made some investments and tried to mitigate the effects of climate, building wells and weirs in his property, but the result was not good enough. Due to the lack of rain, the water that accumulates in those sources can only be drank by animals and, in some cases, be used to water the forage consumed by the animals he raises.

Alexandrino is proud of his property and of his own story. The history of his family is entwined with that of Tauá, and his property, now 2,600 hectares big, used to cover all of the municipal territory. As new generations came, his family gradually lost interest in farm activities. Nowadays he lives there with his wife, and his children (who are in accounting and nursing school) have been thinking of their own career paths.

The property has dairy cattle, sheep and goats. Alexandrino points out that the main highlight is the raising of sheep and goats, a very expensive activity. A lot of money is spent on medicine for those animals; whereas feeding is rather simple.

The farm produces about 700 liters of milk a day. About 400 liters are sold to a milk factory, whereas the other 300 liters are sold in the city center. Between 400 and 600 sheep are sold every year. Alexandrino recalls that his father used to produce about 30 thousand arrobe of cotton, beans and corn, so much it was even difficult to sell everything. That is no longer possible. Due to droughts, agriculture in his property has ended. They are now trying to plant sorghum and milk and wait for scarce rainfall to have something to feed the animals with. Alexandrino strives and does whatever it takes before the winter comes, always hopeful the following year things will be better.

José Roberto Alves also raises goats and cattle, and some hogs and pigs too, in the property he shares with his wife, mother and sister. Besides producing for subsistence, he works selling milk and goat meat. His grandfather and father were cattle and sheep farmers, but raising goats was an idea that he himself followed. That corresponds, nowadays, to almost half of the land output.

A way he found to innovate was to produce flavored cheese, with a variety that ranges from cheese for the hypertensive to that with pepper-like taste. Another tool used to help promote the product is social media. Work on the farm is extremely hard, but it eventually brings the family closer together.

Among the challenges, the expansion of consumer markets

It is not only the trade of animals that moves the economy of the city. on recent years, many economic activities have grown in relevance due to animal products.

Regina Dias, Census of Agriculture coordinator in the state of Ceará, points out that goat farming stands out because semi-arid areas take up “92% of the state. Those animals are the easiest ones to raise given the conditions of our ecosystem; their cost of maintenance is relatively low and the products goats generate have good prices in the market.”

“Goat milk has high nutritional value, it is easy to digest and has twice as many fatty acids as cow milk”, says the head of the nutrition department at University Hospital Walter Cantídio, Ana Kátia Moura. She points out goat milk is contraindicated for persons who are allergic to the protein found in cattle milk and also states that breastfeeding is completely irreplaceable.

The secretary of agriculture of Tauá, Argentino Tomaz, highlights that the goat meat produced there is among the tastiest in the state. That can be confirmed in the streets of the city. One of the most traditional businesses there, Corintiana Steakhouse, has sheep meat as a specialty. Tomaz says most of the goat and sheep production is consumed in the municipality itself, and the exceeding amount is sold to other centers like Fortaleza, Juazeiro do Norte and Picos, in Piauí, for example.

Despite the increase in production, goat farming still needs investments, such as the expansion of consumer markets, for example, to develop completely. That necessity for a bigger number of clients and the establishment of an organized production chain is a desire of many segments involved in the production of goats and sheep, from technicians and scholars to producers and representatives of public spheres. Espedito Martins, from the Embrapa Goat Division, says that “there are initiatives aimed at granting a certificate to the meat produced in the region; they have been trying to obtain a certification of origin for the “Manta de Tauá”.

José Alexandrino believes producers should organize themselves in groups and, with help from the government, strengthen the trade of meat. Before that happens, the product has to be treated as high-value, and not sold to the first middleman that crosses our way."

(*) one of the four sub-regions of the northeast of Brazil, characterized by scrubby vegetation and high temperatures

(**) Embrapa: Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation

Text (in Portuguese and images): Paulo Yan Carlôto, from Ceará

Design: Pedro Vidal