Memory Panel

LSPA: telling the history of Brazilian agriculture for 50 years

April 13, 2023 10h00 AM | Last Updated: April 24, 2023 04h57 PM

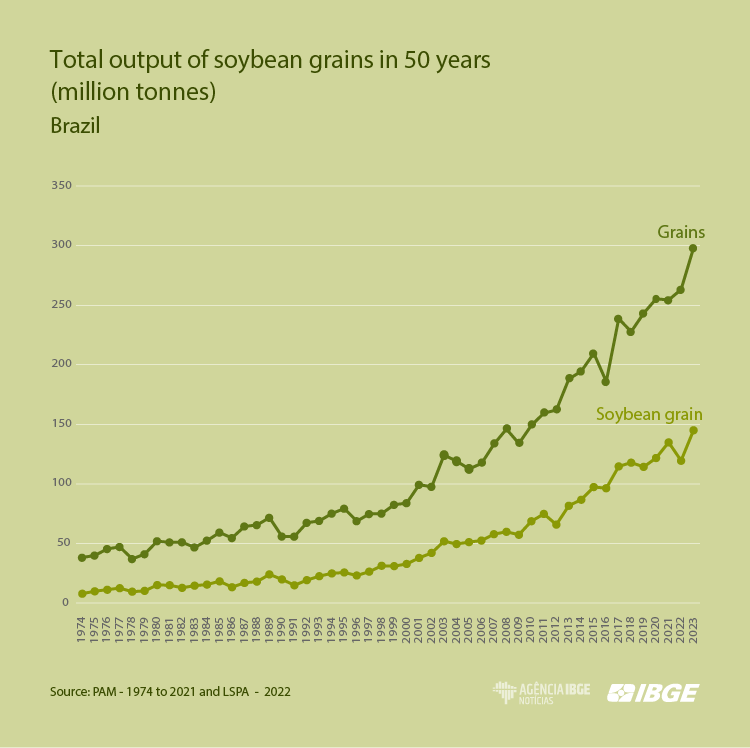

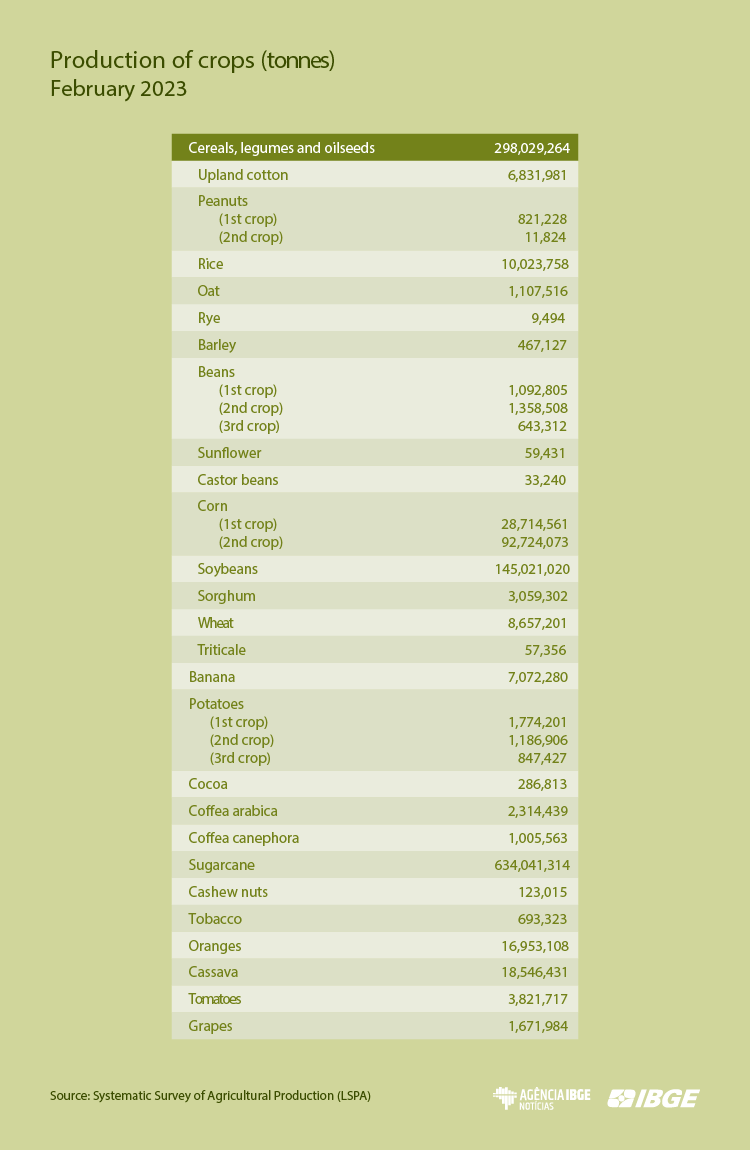

Launched in November 1972, the Systematic Survey of Agricultural Production (LSPA) started its time series in 1975, when Brazil produced 39.4 million tonnes of cereals, legumes and oilseeds. Last year, 263.2 million tonnes were produced and a production of 298.0 million tonnes is expected for 2023.

“The history of the LSPA is the history of the Brazilian agriculture,” highlights Carlos Barradas, who joined the IBGE in 2010 and, in the following year, began to work in the LSPA until taking over its management seven years ago. He tells that the survey originally compiled many products of small economic importance, though they introduced a slitting line in 2016 in order to assess products that accounted for at least 1% of the production value. “From then on, we could better follow up the major products of the Brazilian agriculture,” explains the manager of the LSPA.

Informants network guarantees national capillarity

To collect the data, the LSPA maintains an informants network through the IBGE branches, which count with cooperation of agriculture secretariats, rural unions, cooperatives, major producers and persons who know the agricultural sector in the municipalities. Periodic meetings, the Reagros, discuss the information maintained by the IBGE.

Completing 20 years at the IBGE, Carlos Alfredo Guedes, now an agriculture manager, says that the IBGE has the advantage of maintaining historical data. The planted area of products does not increase much from one year to the other. The survey begins the in the first months of the year, taking into account the history of the municipality: the average productivity and the planted area in the region for a certain product. Informants report the expected increase in the area and the valuation of the product in the market - which should take producers to use more manure or improve crops, otherwise low prices should likely increase the area for another crop.

“All this is discussed in the municipal meetings. IBGE technicians collect the data by means of questionnaires, enter them in the systems and, to consolidate the data, information is edited by state supervisors in the meetings in each state, of which the agriculture secretariats, Emater and other agricultural offices take part. After that, analysts in the headquarters in Rio de Janeiro close the data. The processing is fast. This year, we closed the month on February 28 and released the data on March 9,” explains Guedes.

Training the workforce is a challenge, mainly because the methodology is subjective, requiring a deep knowledge from those who work in the data collection and analysis. Barradas explains that it is hard to say how many people are involved in the data collection for the LSPA, as each IBGE branch (currently they are 566 branches) has a contingent of agents, as well as partners. Pedro Andrade de Oliveira, supervisor of agriculture in Piauí, says that there is a turnover of the temporary Mapping and Survey Agents (APMs) hired in public selection processes. “We encourage everyone who join the IBGE to do the training, even remotely,” says Oliveira.

“The technicians scan the municipalities and each one has a huge amount of informants comprising a national network. No other institution has such capillarity to survey the harvests. The Brazilian agriculture is extremely dynamic and grew a lot. The LSPA tells the history of the evolution of the production of soybeans, corn, rice, beans, cotton. Brazil is one of the most advanced countries in the world in terms of agricultural production and one of the few that still have areas and much water, and should be the major producer of food in the world,” reiterates Barradas.

Transformations of agricultural frontiers were portrayed by LSPA

Jorge Mryczka, supervisor of Agriculture in Paraná, joined the IBGE in June 1979 in this area. Before that, he was already involved with the LSPA as an user and informant. For him, the LSPA is a winner as it is built by the experts network and shows the most real situation in the country.

“The LSPA uses a subjective methodology, though it is built with information from producers, technicians, agronomists, veterinarians and backers, who know the reality of the country. To do this, they obtain information from funded areas, use of fertilizers and seeds, as well as harvesting, trading and exporting data,” describes Mryczka.

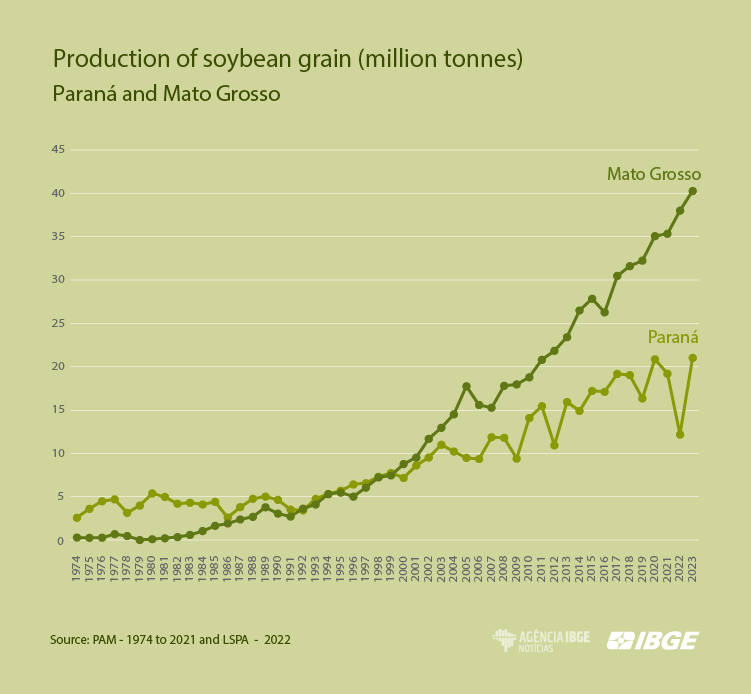

He tells that, when he joined the survey, Paraná was the biggest producer of grains in Brazil and today it is still the second biggest producer, with less than 3% of the Brazilian territory. Among the major crops, the state is the biggest producer of beans. Although the cropped area has been reduced to half over the last years, the productivity of beans triplicated due to the use of new technologies. Corn crops also advanced significantly, growing 50% in areas whose productivity nearly quadruplicated, due to new techniques and new ways of farming.

“Soybeans is the largest cropped area today, having changed from 1.3 million hectares to 5.8 million hectares, an increase of 300%. In 2023, we are expecting a record harvest of 21.0 million tonnes. The productivity doubled due to new technologies, varieties and methods of farming. Wheat crops also doubled the productivity,” describes the supervisor of Paraná.

On the other hand, products were not cropped anymore, like cotton, which has already filled more than 700 thousand hectares in Paraná. Today, no more cotton is planted in the state, having migrated to the Central-West. Paraná was also the biggest producer of coffee until 1975, filling 1 million hectares, when the black frost destroyed all the coffee trees and that crop migrated to Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo. “Those crops required a lot of workforce and the remaining ones are already mechanized. We could follow up all these transformations over these 44 years,” highlights Mryczka.

The IBGE coordinator of Agricultural Statistics, Octavio Costa de Oliveira, talks about the expansion of the crops over the years on IBGE Minute.

Soybeans consolidate Brazilian commercial agriculture

The consolidation of the commercial agriculture in Brazil is mainly due to soybeans. This product was also the major responsible for the acceleration of mechanized crops, modernization of transportation, expansion of the agricultural frontier and improvement of foreign trade. It also contributed to change the diet of the population, internalize urbanization and population of Cerrado.

Soybeans were introduced in Brazil still on the 19th century, though the product strongly expanded from 1973 onwards, with the reduction of the North-American harvest. That scenario fostered the development of a new agricultural frontier in Brazil, by farming soybeans in the Central-Western Cerrado. By 1979, the national output hit 15.0 million tonnes. Between the years of 1970 and 2011, soybeans crop was the one that mostly grew in Brazil, especially in the Central-West, where the output changed from 500 thousand tonnes in 1970 to 44.8 million tonnes in 2011, whereas the growth was less significant in the South.

In 2022, soybeans hit an expected production of 119.5 million tonnes and should reach 145.0 million tonnes in 2023. The advance in soybeans farming in Brazil followed the growth of the foreign demand, especially from China, which became the biggest importer of the Brazilian oilseed in the late 1990s. Today, soybeans is the major item of the Brazilian exports.

“This significant historical rise is mainly due to the migration of farmers from the South to the Central-West, and Mato Grosso is the biggest producer today. From 2000 onwards, it expanded to Matopiba, where the production grew a lot since then,” completes Guedes.

Pedro Nessi Snizek Junior, supervisor of Agriculture in Mato Grosso, joined the IBGE in 2002 in the area of agricultural surveys, whose supervision he took over in 2009. He tells that soybeans crops in the region began in the municipality of Dourado, currently belonging to Mato Grosso do Sul, from the development of new varieties by Embrapa. Farmers from Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina and Paraná who migrated to the region took varieties from the South that even sprouted, but did not produce anything. Embrapa began to produce new varieties and soybeans gained strength from 1986 onwards.

“Today, Mato Grosso produces between 9% and 10% of the soybeans in the world. If that state were a country, it would be the third or fourth biggest producer. We have very representative municipalities, like Sorriso, Campo Novo dos Parecis, Sapezal, Querência and Nova Ibiratã. Mato Grosso accounts for 30% of the national output of soybeans, due to the technological development in the 1970s, major migration flow in the 1980s and mechanization in the 1990s. These producers sold an area with 50 hectares in the South and bought another one with a thousand hectares in Mato Grosso, pioneering the region. In 2022, that state accounted for an output of 38.3 million tonnes; in 2023, it is expected a production of 44.0 million tonnes,” analyzes Snizek Jr.

In the new agricultural frontier, Matopiba, the output grows by 10% per year. Today, agribusiness represents 90% of the production of grains in Piauí, according to Pedro Andrade de Oliveira, supervisor of Agriculture in that state. He joined the IBGE 45 years ago, in July 1978, working the data collection network, including the processing of LSPA data, which had been created six years before. From 1991 onwards, he began to work as a survey supervisor. Along 30 years, he has been following up the work of nearly five annual meetings in all the 224 municipalities of that state in order to follow up the agricultural production.

“As we are in the semiarid, the production in Piauí and in the Northeast are jeopardized by climate conditions, as the rule in these areas is the lack of rainfall. Whenever a period is good, like in the last three years, the harvests have been standing out. Local agriculture is usually familiar, though the first major producers arrived in the 1990s to plant rice, later replaced by soybeans. We had the privilege to follow up that transition. We visit these producers at least once a year, not forgetting to look at family farming in these meetings with unions, secretariats of agriculture and funding offices,” highlights the supervisor of Agriculture in Piauí.

Vegetal improvement allowed agricultural expansion in the entire country

Several factors contributed to the growth of the Brazilian agricultural production. Among them are governmental incentives, improvement in agricultural techniques, rising foreign market and significant replacement of animal fat traditionally used in food by vegetable oils. It should also be mentioned the development of a major industrial park to produce inputs and process grains, creation of a cooperative network, improvements in the transportation system and advances in scientific research after the creation of Embrapa. The state-run agricultural company developed seeds more adapted to the Brazilian soil, opening ways for crops to reach the Cerrado areas.

“Embrapa was important because the Central-Western soil was very limited, and the company developed varieties that adapted very well. The technological advance allowed Brazil to crop three harvests in the year, an unprecedented endeavor in the world. This is due to vegetal improvement and reduction in the production cycle. The new varieties can be planted and harvested in less time and larger amounts. And there is the marriage between different crops, which follow each other: once soybeans is harvested, corn is planted. The production costs of the Brazilian soybeans are lower than the American ones, since that aside the genetic improvement of the varieties, we developed the biological nitrogen fixation as well. In 2020, we became the biggest world producer,” highlights Barradas.

Direct planting favored and sped crops

Alfredo Guedes highlights the national development of the technique of direct planting, by means of machines that plant without revolving the soil. It favored and sped the Brazilian crops. Producers plant soybeans in October and harvest in the first semester, then, right after harvesting, they plant corn.

“Direct planting is a way to protect the soil, maintaining haystacks from the previous crop to protect the land and to cycle nutrients, which are used in the next crop. Mechanization advanced as well. In the beginning, the machines had six lines; today, they have 36 lines. Investment is huge, the machines are expensive, yet producers have many areas and are capitalized to acquire this equipment. Family farming also evolved, adopting mechanization to plant and harvest, and organizing in cooperatives. Agriculture evolved both among big and small producers,” assesses Guedes.

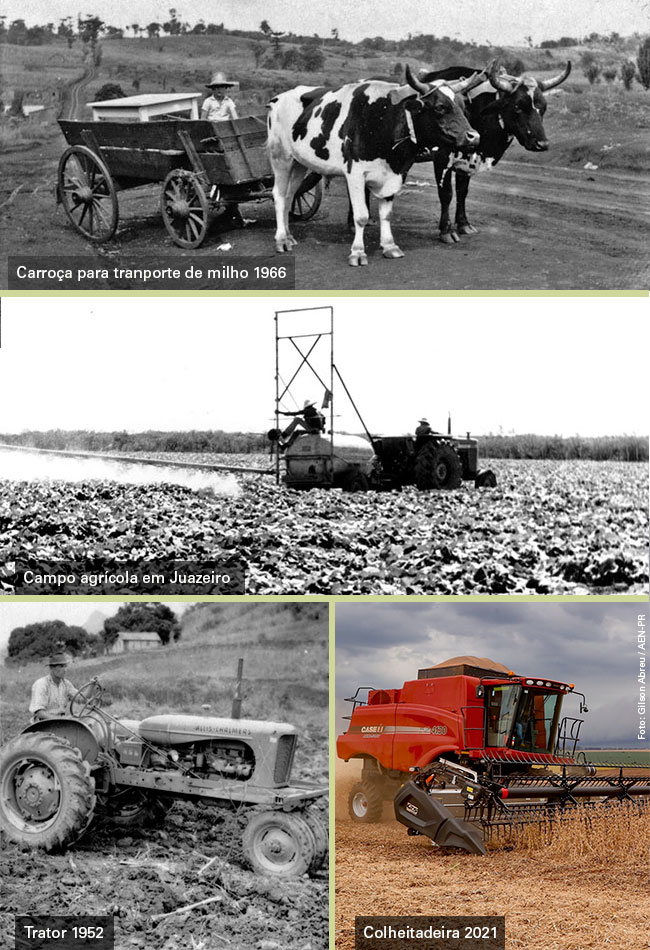

With the technological advance, the professional profile changed as well. Rural workers manually harvesting were replaced by machine operators. Rural exodus also contributed to changes, as many people moved to cities looking for better work conditions.

“The number of persons who want to work in the country began to decline; many times, sons of producers don´t want to stay. The lack of workforce is a problem, and many producers change manual workforce for machines. Some crops, like coffee, still need a lot of workforce, as well as the areas in which the equipment does not reach,” completes Guedes.

From mechanization to digital transformation

After the advance of the mechanization, the new technological revolution is precision agriculture through digital transformation of the country with new resources like drones, Internet of things (sensors connected to monitor different aspects of crops) and satellite images.

“Today, the entire population is connected through cell phones and producers are not different. They advanced a lot with techniques of remote sensing, satellite images, use of drones to pinpoint places with diseases or to apply products. In addition to the control of plagues and plant diseases caused by natural enemies, the analysis of the soil, made in laboratories, already allows the distribution of manure in the exact places where it is needed,” enumerates Guedes.

The new technologies brought other challenges, like connectivity in the country, which begins to be addressed with the installation of 4G mobile networks and, soon, 5G. “Precision agriculture is pure technology. The technological evolution began with direct planting, which exempts the work of plowing and griding land, maintaining the original structure of the soil, thus mitigating erosion problems, as well as reducing expenditures with energy, time and work,” highlights Barradas.

The new agricultural frontiers also brought logistic challenges, which are being overcome by new exporting routes through the ports in the North Arch, avoiding the transportation of the production for up to two thousand kilometers until the ports of Santos, in the Southeast, and of Paranaguá, in the South.

Pedro Andrade de Oliveira, supervisor of Agriculture in Piauí, informs that the local production is currently flown by road until the ports of Pecém, in Ceará, and Suape, in Pernambuco. For him, the production of family farming still needs to evolve.

“Despite the efforts the governments do to encourage family farming, it doesn´t take off. What is produced today is the same as 30 years ago. The particular agricultural production of Piauí evolved to agribusiness,” says Oliveira.

Brazilian agriculture can grow without damaging the environment

Some consider that the expansion of soybeans in Brazil negatively impacted the environment and the society, including high indexes of deforestation, land concentration and losses to family farming. For Barradas, it is possible to reconcile agricultural growth and environmental preservation.

“The way of the Brazilian production is to grow even more without deforesting areas or degrading the environment. We still have many misused pasture areas, which can be useful to agriculture. We don´t need to remove forests and damage nature. Technology is the mark of our agriculture, the increase in the area is irrelevant compared with the increase in the productivity. When I graduated, the productivity of corn was three tonnes per hectare, today it is 11 tonnes; that of soybeans was two tonnes per hectare, today it is four. Brazil already produces food for more than 1 billion people and it has climate advantages and technology. The evolution of the Brazilian agriculture is natural, the world requires that Brazil produces food,” considers Barradas, manager of the LSPA.

IBGE surveys Brazilian agriculture since its foundation

The IBGE surveys the Brazilian agriculture since 1938, when it carried out the first data collection, at national level, using a single subjective method of estimates. They were accomplished at the end of each calendar year, based on data of the agricultural production in the last harvest. From 1944 onwards, the survey began to be accomplished on a quarterly basis, showing the estimates related to the harvests closed in the quarter and the expected harvest underway.

In 1962, the Ministry of Agriculture created the Harvest Forecast Service (SPS), which, in 1964, started its activities testing registries of the Territorial Tax and of the Census of Agriculture. Based on subjective estimates, the survey encompassed 16 products and took place in 21 states, forecasting harvests at planting, harvesting and off-season time. In 1966, the Ministry proposed an experimental sampling survey. In 1969, the National Plan of Agricultural Statistics was created, improving the use of the sampling method in the technical area.

In 1972, subjective surveys began to be gradually replaced, at the municipal level, by a new statistical system with probability samples (at the producer level). The gradual replacement didn´t occur and, as a consequence, the IBGE implemented the Systematic Survey of Agricultural Production (LSPA). The survey completed 50 years in 2022 and, along this half century, it has been portraying the evolution of the national agricultural production.

“The LSPA was created in 1972, when Brazil passed through a complicated situation in the statistical area. Since 1938, the IBGE collected information, but the dissemination was in charge of the Ministry of Agriculture,” says Carlos Alfredo Guedes, who completes 20 years at the IBGE and is currently the manager of Agriculture.

That model remained until the early 1970s, when the statistics began to be collected, processed and released by the IBGE. It required a survey that followed up the agriculture on a monthly basis, which resulted in the LSPA, which uses a subjective methodology also adopted in other countries.

“Few products were surveyed in the beginning, around 12, then the LSPA managed to survey up to 36 products. A revision was made in the last years, and it resulted in 25 products released. They are the major items, those with the highest production value of the Brazilian agriculture: soybeans, corn, beans, cotton, rice, sugarcane, coffee and orange, among others,” tells Guedes.

“It is hard for a survey to reach 50 years in Brazil. The best answer comes from the market.”

Neuton Rocha joined the IBGE in 1977 and accumulated 30 years working in agricultural surveys. He tells that slightly before that Cepagro (Special Commission on Planning, Control and Assessment of Agricultural Statistics) was created, which originally designed the LSPA in 1972. Then the Deagro (Department of Agriculture) was created, centralizing the information and creating the LSPA in April 1973, as well as the Comeas, the meetings in the municipalities.

“In the beginning, it was very hard to obtain the information from the municipality. I highlight important names for the survey, like Manoel Monteiro, Raul Ehlers, Calos Lauria, Flavio Pinto, Noel, Elvio Valente, Paulo Renato, Roberto Augusto, Claudio Peixoto, Teresinha, Tadeu, Teresa, Octávio Oliveira”, reminds Rocha.

“At that time, few agricultural and livestock statistical data were available. Society then required short-term monthly data on area, production and productivity of the major crops, like corn, rice, beans, cotton and soybeans, then in its early stage in the early 1970s,” highlights Rocha.

He says that the LSPA was responsible for creating groups of agricultural statistics, involving a complex system with different workgroups in the states and municipalities.

“It requires flexibility to gather everybody to those meetings. Despite all the difficulties, the LSPA has been surviving along these 50 years. If you want to know the Brazilian agriculture in this period, be patient and research the minutes of those meetings. Every month new data are produced on the national agriculture,” suggests Rocha.

Besides the creation of the LSPA in 1973, Embrapa, the Brazilian company in charge of agricultural research, was created as well. Tracing a parallel between the creation of the survey and of Embrapa, you notice the evolution of the Brazilian agriculture by means of new techniques like direct planting.

“Today, that practice was spread along all species of grains in the entire country. When soybeans began to be planted in the 1970s, the productivity was slightly above 1 thousand kg per hectare; with new advances and new varieties created by Embrapa, the average productivity is currently 3.6 thousand kg per hectare. Twenty years ago, we would like to celebrate the goal of 100 million tonnes. The estimate for 2023 is nearly 300 million tonnes of grains and it will grow forever. If we cross the curves of area with that of productivity, we notice that that of area remains virtually unchanged and that of productivity advances,” highlights Rocha.

To answer those critics of the subjective method and repetition of data, he highlights the challenge of gathering, every month, experts and persons involved with agriculture in all the Brazilian municipalities to produce a consensual information.

“A consensus of the month´s production is achieved in those meetings. As a consensual data, the LSPA doesn´t measure the error. Yet, there is no other survey like the LSPA, resisting for 50 years. It is hard for a survey to reach 50 years in Brazil. The best answer comes from the market. Whether big or small, the market doesn´t accept any error; and the market has never spoken up so much about these data. That is because, whenever soybeans groan here in Brazil, the Chicago Stock Exchange has woken up a long time ago. Whenever coffee groans in Brazil, the London Stock Exchange has woken up a long time ago,” warns Rocha about the commodification and globalization of the agribusiness trade.

“The persons who work in the LSPA are high-level careful technicians, who provide quality to the information”.

José Garcia Gasques, general-coordinator of Public Policies of the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock, is one of the old users of the Systematic Survey of Agricultural Production (LSPA), firstly at the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA) and then assigned to the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock to work in long-term projections, where he works today as general-coordinator of Public Policies. He tells that the LSPA was already used as a basic material in the Cepagro meetings.

“We have a very strong relationship with the LSPA as an user of the survey, which passed through huge changes in the Brazilian agriculture, like the creation of Embrapa in the early 1970s and its growth. The survey is important because it is a periodic and punctual surveying with a big number of products from permanent and temporary crops,” says Gasques.

He tells that the Ministry uses the LSPA in a number of other surveys, like the monthly calculation of the gross production value (VBP), which investigates crops and agricultural items. The matching of the LSPA information with the annual surveys, like PAM (Municipal Agricultural Production) and the PPM (Municipal Livestock Survey), allows to obtain another important indicator, the Total Factor Productivity (TFP).

“The Total Factor Productivity index is very relevant as it allows international comparisons of productivity, which would be very difficult with other indicators. Today, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is matching traditional factors, used in the calculation of the productivity, with sustainability factors, like erosion and climate changes,” highlights Gasques.

He notes that the analyses on the agricultural sector in the quarterly GDP (Gross Domestic Product) surveys are based on the LSPA. “We use these analyses to pinpoint crops that mostly contribute to the national accounts. We also use the LSPA in long-term projections, which use econometric models. As nearly 30 products are analyzed, the LSPA and CONAB surveys are the basis for the selection of these products,” completes the coordinator of Public Policies of the Ministry of Agriculture.

He says that the subjective information is practical and fast and that the differences the data observed and surveyed are generally small, unless an extraordinary fact like climate events occurs, which can move the data away from the average. “The persons who work in the LSPA in the state offices are high-level careful technicians, who provide quality to the information” concludes Gasques.